Terminology is the connective tissue of knowledge work. When unmanaged, it creates inefficiency, inconsistency, and risk. When deliberately captured and shared, it becomes a force multiplier—reducing friction, improving clarity, and preserving institutional knowledge.

In knowledge-intensive environments—academia, law, healthcare, engineering, policy, and enterprise—terminology is not a stylistic concern. It is infrastructure. Terminology encodes shared meaning, reduces ambiguity, supports compliance, and enables collaboration at scale. Yet despite its centrality, terminology is typically managed informally: embedded in documents, held tacitly by individuals, or rediscovered repeatedly through ad hoc searches.

This gap reflects a broader issue in knowledge work: while significant investment has been made in content creation tools, comparatively little attention has been paid to the systematic capture and reuse of language itself.

The consequences of unmanaged terminology are well documented across knowledge management and technical communication literature. Common failure modes include inconsistent usage, conceptual ambiguity, duplicated effort, and increased editorial overhead (Cabré, 1999; Wright and Budin, 2001). In regulated domains such as law and healthcare, inconsistent terminology can also introduce material risk, affecting interpretation, compliance, and defensibility (ISO, 2019).

When terminology exists only within individual documents or personal memory, organisations experience what Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) describe as knowledge loss through tacitness—critical expertise that is neither externalised nor transferable.

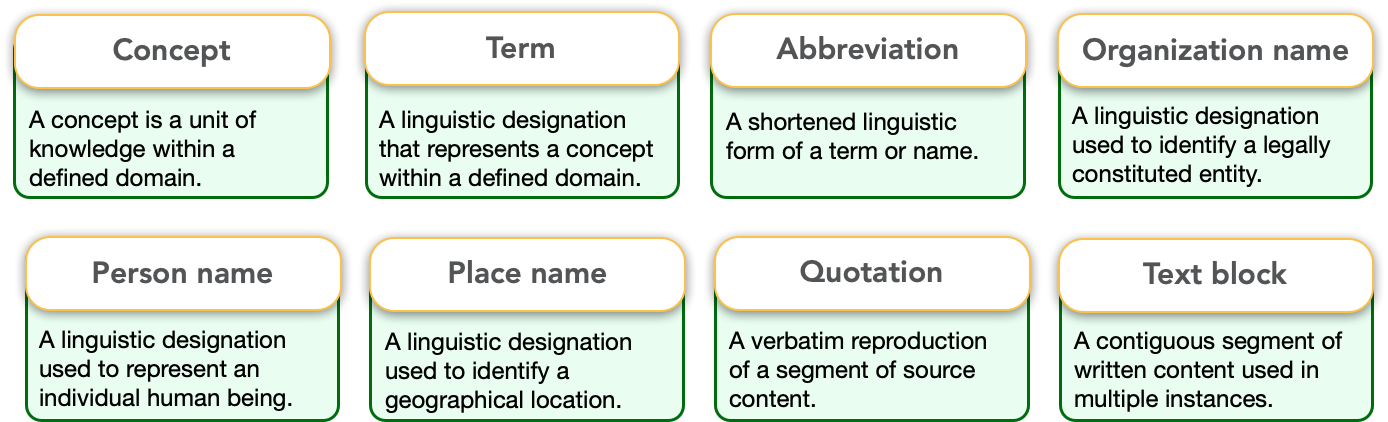

Reusable terminology is often misunderstood as synonymous with a glossary. In practice, it is better understood as a managed semantic layer that sits between individual documents and broader knowledge systems.

Effective terminology systems provide:

From a strategic perspective, terminology management aligns with broader knowledge governance practices, transforming language into a reusable organisational asset rather than a by-product of writing (Davenport and Prusak, 1998).

Most professionals already engage in informal terminology capture:

These practices indicate demand, not maturity. The limitation is that such artefacts are rarely integrated into writing workflows or shared systematically. As a result, terminology remains fragmented, difficult to govern, and vulnerable to drift over time (Temmerman, 2000).

Research in terminology science emphasises that for terminology to be effective, it must be embedded in use, not merely documented (Cabré, 1999).

A growing body of research suggests that competitive advantage increasingly depends on linguistic consistency and knowledge reuse, particularly in complex and regulated environments (Wright and Budin, 2001; ISO, 2019).

Reusable terminology enables:

In scholarly and professional contexts, this also supports auditability—the ability to demonstrate that language choices are deliberate, standardised, and aligned with accepted definitions or authorities.

Best-practice terminology systems move beyond static glossaries to support:

Critically, such systems support authorship rather than constrain it. Terminology guidance functions as decision support, not enforcement, preserving nuance while reducing avoidable inconsistency (ISO, 2019).

The rise of collaborative authoring platforms and AI-assisted writing has intensified the need for explicit language governance. While AI systems can generate fluent text, they cannot infer organisational or disciplinary preferences without structured inputs.

Reusable terminology is the mechanism by which human expertise is operationalised for both people and systems. It enables organisations to externalise linguistic knowledge in a form that is scalable, teachable, and reusable (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995).

Terminology is the connective tissue of knowledge work. When unmanaged, it creates inefficiency, inconsistency, and risk. When deliberately captured and shared, it becomes a force multiplier—reducing friction, improving clarity, and preserving institutional knowledge.

The next evolution in writing platforms will not be defined solely by better grammar or style checking. It will be defined by systems that understand, preserve, and operationalise the language that matters most.

Organisations that invest in reusable terminology are not merely improving how they write. They are codifying how they think—and ensuring that thinking can be shared, reused, and sustained.

Cabré, M.T. (1999) Terminology: Theory, Methods and Applications. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Davenport, T.H. and Prusak, L. (1998) Working Knowledge: How Organizations Manage What They Know. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

ISO (2019) ISO 704: Terminology Work — Principles and Methods. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995) The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Temmerman, R. (2000) Towards New Ways of Terminology Description: The Sociocognitive Approach. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Wright, S.E. and Budin, G. (2001) Handbook of Terminology Management. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.