A strong academic or professional document requires balancing breadth—the range of material covered—with depth: breadth ensures comprehensiveness and contextual awareness, while depth demonstrates intellectual rigour and mastery.

Long-form writing, whether in the form of theses, research articles, policy reports, or technical documentation, presents unique challenges. Chief among these is balancing breadth—the range of material covered—with depth—the level of detailed analysis applied to specific elements. A strong academic or professional document requires both: breadth ensures comprehensiveness and contextual awareness, while depth demonstrates intellectual rigour and mastery.

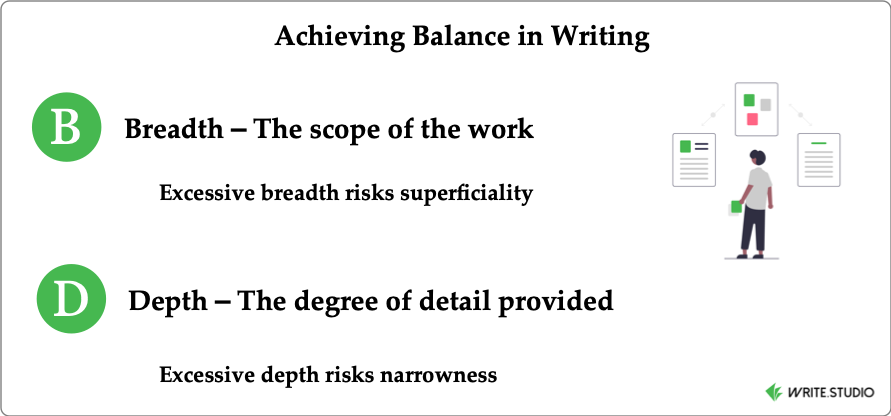

Breadth refers to the scope of coverage in a written work. It is concerned with how widely a document engages with relevant themes, perspectives, and evidence.

Breadth functions as a marker of credibility: it signals that the writer is aware of the field’s diversity and has critically surveyed its terrain.

Depth, by contrast, reflects the degree of detail and analysis applied to selected aspects of the subject. Depth requires moving beyond description to analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.

Depth is what lends authority and persuasiveness to a document: it demonstrates not only that the writer understands the broader landscape, but also that they can interrogate it at a granular level.

The tension between breadth and depth is well recognized in both education and cognitive science. Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives (Bloom et al., 1956; Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001) emphasizes the need to move from broad knowledge acquisition to deep critical analysis and synthesis. Similarly, cognitive load theory suggests that writers must balance scope and complexity so that documents remain comprehensible without oversimplifying (Sweller, 1994).

In practice:

Thus, effective long documents require calibration: enough breadth to establish context, enough depth to provide insight.

Breadth and depth are not competing dimensions but complementary requirements of effective long-form writing. Breadth situates the work within a wider intellectual or practical field, while depth demonstrates critical engagement and originality. Balancing the two is central to producing writing that is not only comprehensive and credible but also analytically rigorous.

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. Longmans, Green.

Booth, W. C., Colomb, G. G., & Williams, J. M. (2008). The craft of research (3rd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

Cottrell, S. (2019). The study skills handbook (5th ed.). Red Globe Press.

Hart, C. (1998). Doing a literature review: Releasing the social science research imagination. Sage.

Sweller, J. (1994). Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learning and Instruction, 4(4), 295–312.