Clear, persuasive communication is a cornerstone of both academic and professional life; the ability to construct a compelling argument determines how effectively ideas are received.

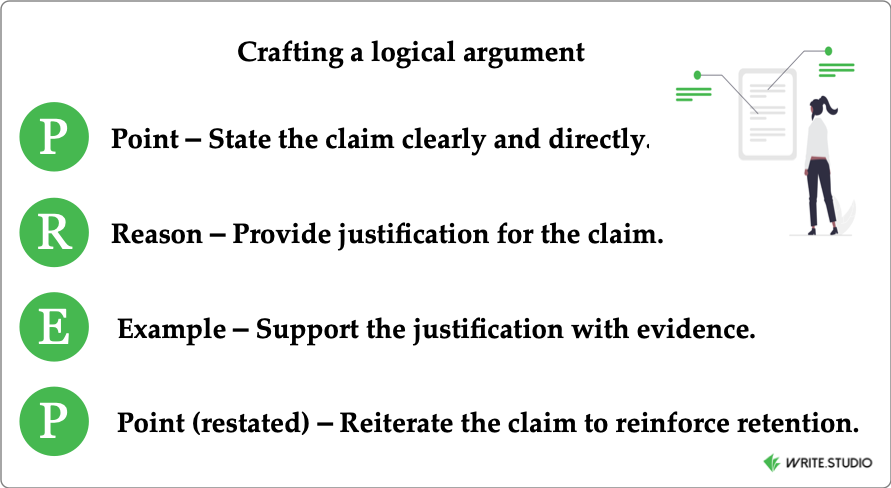

Clear, persuasive communication is a cornerstone of both academic and professional life. From seminar discussions to research presentations, the ability to construct a compelling argument determines how effectively ideas are received. One widely taught framework for structuring arguments is the PREP method—Point, Reason, Example, Point (restated). While often associated with business communication, its foundations are consistent with well-established principles of rhetoric and argumentation theory.

The PREP method offers a concise rhetorical structure:

This structure mirrors classical rhetorical traditions. Aristotle’s Rhetoric emphasised the importance of logos (logical reasoning) supported by examples (paradeigmata) to enhance credibility, while contemporary argumentation theory highlights the role of evidence in strengthening claims (Toulmin, 1958).

Research in cognitive psychology suggests that information structured in predictable patterns is easier to process and retain (Sweller, 1994). The PREP model reduces extraneous cognitive load by guiding the audience through a linear, logical sequence.

Stephen Toulmin’s (1958) model of argumentation identifies claim, grounds, and warrant as essential elements of a strong argument. PREP aligns neatly with this framework:

By beginning and ending with the same central claim, PREP leverages the primacy and recency effect, where audiences are more likely to remember the first and last elements of communication (Murdock, 1962). This repetition strengthens persuasion.

Imagine a student presenting in a seminar on renewable energy:

PREP is a concise yet evidence-based structure that communicates a clear argument while inviting further discussion. These four statements, structured this way, provide a coherent and logical paragraph.

School students are often taught the OREO method of argument which provides a different acronym for the same approach. APSU (2024) explains how each part contributes to building a well-rounded paragraph:

The previous example is restated using the OREO method:

As a writer, either method is suitable; it depends on which method you feel more comfortable using as an appropriate memory jogger.

While PREP is effective for short-form arguments (e.g., presentations, interviews, discussions), it may oversimplify more complex academic debates. Extended essays and research papers typically require multi-layered reasoning, counterarguments, and detailed evidence beyond the scope of PREP. Thus, PREP is best understood as an entry-level framework for structured argumentation rather than a substitute for comprehensive critical analysis.

However, if a cadre or arguments, and counter-arguments, are strictured in this way, each individual argument contains a sufficient level of logic and reasoning. LInking each paragraph together ensures the line of argument is also coherent.

The PREP method remains a valuable tool for structuring arguments in academic contexts, particularly when brevity and clarity are essential. Its alignment with rhetorical tradition, cognitive principles, and argumentation models explains its enduring effectiveness. By mastering PREP, students and researchers can communicate persuasively in seminars, conferences, and professional discussions, while recognising when more sophisticated frameworks are required.

APSU Writing Center. (2024). Paragraph formatting with OREO method [PDF]. Austin Peay State University. https://www.apsu.edu/writingcenter/writing-resources/Paragraph-Formatting-OREO-Method-2024.pdf

Aristotle. (2007). On Rhetoric: A Theory of Civic Discourse (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Murdock, B. B. (1962). The serial position effect of free recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 64(5), 482–488.

Sweller, J. (1994). Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learning and Instruction, 4(4), 295–312.

Toulmin, S. (1958). The Uses of Argument. Cambridge University Press.